Week Two of a weekly syllabus/reader for the creative nonfiction course I’m building in real time to document what my Dartmouth colleague Jeff Ruoff dubs “the Trumpocene,” as experienced by students and residents of our region. It’s called “The Reporters.” Here’s Week One.

Week Two: It’s Obvious.

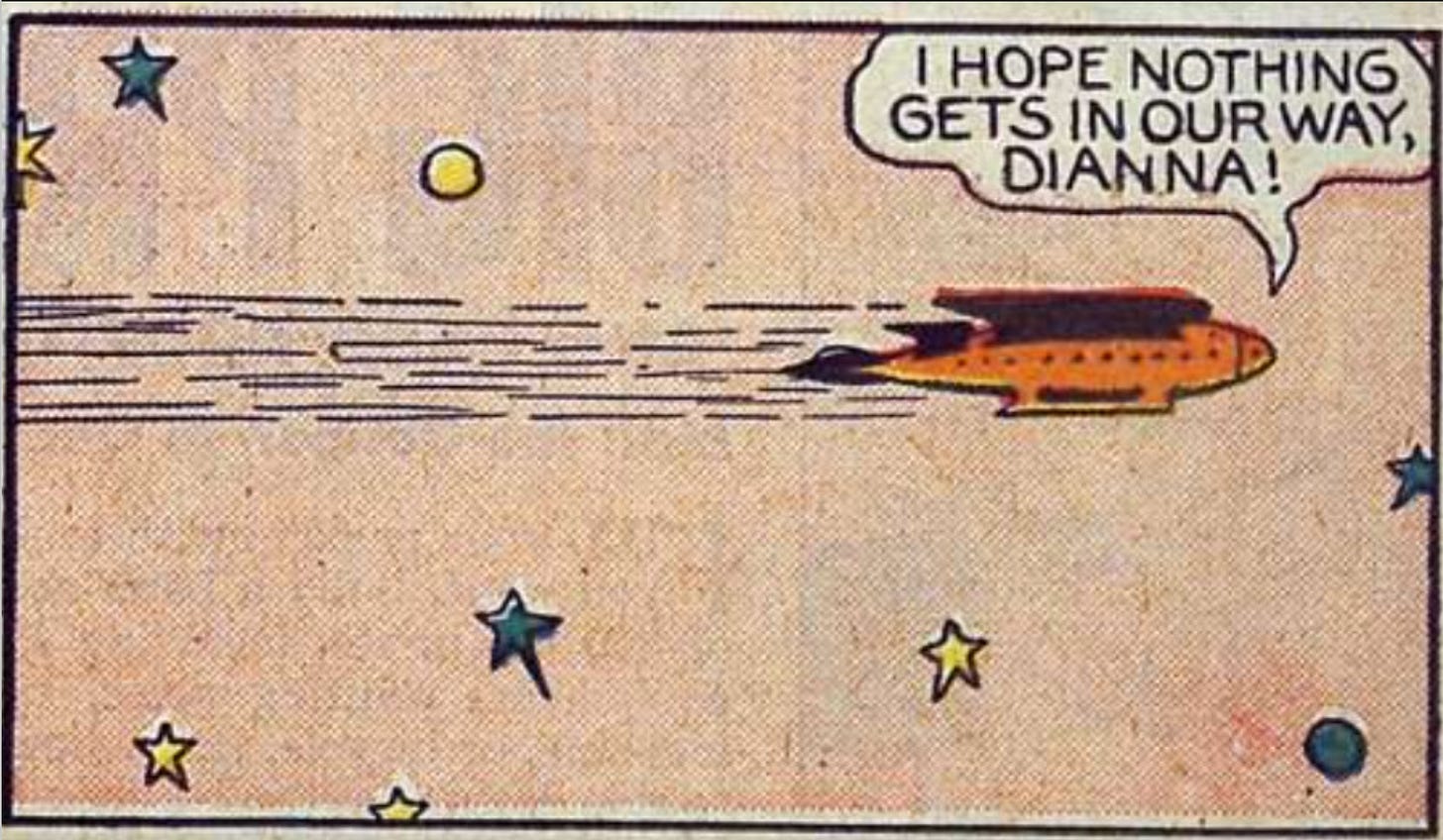

“Something is already in our way.”

We’ll dedicate our second week to one of the first rules of creative nonfiction: state the obvious. That is, write what you see; or what you know; or what you want to know; or fear, or suspect, or wish for, or what someone else knows, or fears, or wishes for. Write what you perceive. Take nothing for granted.

I’m illustrating this ambition with what some see as the most literal of forms: a comic book. Nothing fancy, not a graphic novel; a cheap pulp fiction story by one “Hank Christy”—a pseudonym—about the adventures of a pair of explorers named “Space” Smith and Dianna, from the April 1940 edition of Fantastic Comics. I like these old-timey comic strips because they’re so simple, so obvious.

Here’s a little etymology of that term:

1580s, “frequently met with” (a sense now obsolete), from Latin obvius, “that is in the way, presenting itself readily, open, exposed, commonplace,” from obviam (adv.) “in the way," from ob, “in front of, against” (see ob-) + viam, accusative of via, “way” (from proto-Indo-European root wegh-, “to go, move, transport in a vehicle”). Meaning “plain to see, evident” is recorded from 1630s.

Comics artists refer to the space between panels as “the gutter,” an unassuming term which disguises the creative collaboration by which the reader leaps from image to image. Comics are words and pictures, static on a page, yet the reader sets them in motion. From one panel to the next, we see the action—and yet not, as in a movie, each movement. Our imaginations fill in the distance from one panel to the next. So, too, when we read prose: we collaborate with the writer to make meaning of strings of letters arranged into strings of words.

To state the obvious is to engage in collaboration with what’s there. It’s to engage with the imagination, moving us from one panel to the next, one fact to another. “Real toads,” as the poet Marianne Moore put it, in the imaginary gardens of our perception.

Here’s the next panel of the comic strip:

Is there ever!

What will happen next? That’s the story. That’s what we’re trying to find, each of us, our own stories. One good way to start is by attempting to perceive the obvious. This week: What’s in the way.

Reading:

Method: “Artists in Uniform,” by Mary McCarthy, Harper’s Magazine. When I published this in an anthology of literary journalism, I focused on McCarthy’s craft, particularly with regard to symbolism in nonfiction. That’s still worth looking at. But right now, in a time when “dialogue” refers not so much to telling a story through multiple speakers as a polite-at-all-costs means of “listening” to the “other side,” we’ll also read McCarthy’s sharp-edged dialogue with a bigot on a train—and with her own failings to meet the moment—to for what we may learn about how to hear hate, even when it’s well-mannered.

Method: excerpts from This Is All I Got: A New Mother’s Search for Home, by Lauren Sandler. A sociologist might say this is a book “about” homelessness and a broken social welfare system. That’s in there. But we’re reading it for Sandler’s art: the intimacy of portraiture, the fine line of first-person limited, the ways in which the “aboutness” of “social issues” might be better seen in the fullness of a life, closely and tenderly observed.

Lauren Sandler will be joining us by Zoom—come prepared with questions. Bio:

Sandler is the author of two previous books, the bestselling One and Only, and Righteous: Dispatches from the Evangelical Youth Movement. She is currently reporting and writing a book about an ideologically divided Southern family as a way to understand our current political climate, called American Prophecy: One Family, Two Nations, and a World on Fire. She’s also been at work on a musical — co-writing with playwright Kirsten Greenidge and composer Crystal Monee Hall — based on her reporting in a Brooklyn shelter, called Shelter in the Promised Land.

Perception: excerpts from The Third Reich of Dreams, by Charlotte Beradt

Data. This work isn’t creative nonfiction, but it will help us understand the moment. Some of it is perfunctory (Politico), some of it exemplary reporting (Mother Jones), some of it work of another genre (Osman’s poem), and some of it we might view as “primary source material,” such as the case against birthright citizenship made by Dartmouth’s new Trump-aligned general counsel, Matthew Raymer.

--“Trump is bombarding the Ivy League…,” by Myah Ward and Irie Sentner, Politico

--“Trump is Right About Birthright Citizenship,” by Matthew Raymer, The Federalist

--“The Plot Against Birthright Citizenship,” by Isabela Dias, Mother Jones

--“Birth Country,” by Jamila Osman

Listening: “The Museum of Now,” This American Life

Writing: We’ll be working throughout the term toward a long, reported, narrative story about the strange contingencies of this particular moment in time in this particularly strange place—the Upper Valley of New Hampshire, and Vermont, broadly speaking. Our assignment each week is to complete at least 4-5 pages toward that end. Your assignment this week is to choose one of the following.

A) State the obvious; or, write a story of perception and what’s in the way, for you or your subject.

B) Continue from Week One.

Looking: The obvious. Works by graffiti artist Banksy and photographer Susan Meiselas, below. Some of it is polemical art. That’s sometimes taken as a pejorative. At its most fruitful, as below, it’s a productive tension, a paradox that can remake as strange and startling ideas that might otherwise be taken for granted.

Sometimes the obvious gets complicated. Below, somebody else’s snapshot of what may be the first iteration of Banky’s most famous work. A masked man who appears to be throwing a Molotov cocktail—only, upon a closer look, we see he holds instead a bouquet of flowers. Hence the name by which this image is known, here, in the West Bank, and in versions painted around the world, some by Banksy, some by tribute artists, and on posters and t-shirts and mugs. It starts obvious – it’s the West Bank, a rebel fights with a homemade weapon. It becomes complicated – he’s throwing flowers, oh, how lovely, wait, does this mean he’s giving flowers to his enemy, or that the beauty of a bouquet, beauty itself, is the weapon, also homemade? Is this anti-war or pro-war, is this about the one who throws or that which he throws or is it an invitation to imagine that at which he throws—a tank? A building? A body? What will happen next?

Another question: What happened before? Like any artist, Banksy takes inspiration from forms that precede his own work. Some speculate that the flower thrower is a visual descendent of another iconic image, “‘Molotov Man,’ Esteli, Nicaragua, July 16, 1979,” by Susan Meiselas:

Let’s complicate that, because the obvious isn’t always simple. Follow this link: https://www.susanmeiselas.com/nicaragua-molotov

Now scroll sideways.

It’s like a comic strip.

Your looking assignment: Make a screenshot of a panel of one of Meiselas’s many scrolls. You can choose from “Molotov Man” or any other of Meiselas’ projects: https://www.susanmeiselas.com/all-projects. Print the screenshot and add it to your syllabus below, along with your notes about why you chose as you chose.

Some possibilities:

From Prince Street Girls

From “Cova da Moura, Portugal”

How I would have loved to have taken this class when I was young. Thank you for posting this. Many years ago I read a series of interviews of Paulo Freire by Ira Shor, and I still remember the feeling of excitement about the potential for education to stimulate wonder, understanding and agency. I experienced the same feelings when I read through this syllabus excerpt. Outstanding.