Detail from an erasure in Natasha Trethewey’s essay, "Ground Truth.”

The new term has just started at Dartmouth College, where I’m a professor of creative writing, and with it a new variation on one of my creative nonfiction classes. It felt necessary last term to address in my creative writing courses the political changes challenging the way we use language and what happens in classrooms and who gets to be there. This term I decided to build a course around these questions. But since I teach creative nonfiction, not political theory, we’ll address them by writing narratively about the changes happening all around us—on our campus, in our community. I’m calling the course The Reporters. In lieu of a course description, I wrote a little story:

Once I co-taught a workshop for writers and activists with a legendary organizer who told us a story about making art in dangerous times. Her art was community; she’d helped create a queer feminist commune in rural Arkansas. Late ‘70s, early ’80s. Local women started coming to the commune for help—to get away from violent men. The organizer and her friends took the women in. Men followed. The men wanted to “take back” women they considered theirs. Some had guns. Move aside, they said. The organizer—she was very small—and her friends stood their ground.

A young writer listened, wide-eyed. “That’s so beautiful!” she told the organizer. “You made a safe space!”

The organizer, an old woman now, reached over and put a soft hand atop the young writer’s. The old woman’s manner was of another century; she had been raised on a farm, and her voice really was like sweet tea.

“Oh, honey,” she said. “There are no fucking safe spaces.”

And yet, she told us, there are stories we make together that can be moments of something like safety—pauses between fight or flight in which we might consider what we know of the world and how we know it. The cultivation of such moments—in our classroom, on the page—is the aim of this course, conceived in response to what your instructor will argue is as the accelerating disappearance in the United States of words, images, and even people.

Our focus will be on how such changes ripple through our region. Through weekly conversations with working journalists and other documentary artists, we’ll contemplate how to tell true stories in an age of erasure. We’ll share our best attempts to do so publicly.

Students of all politics, or none, are welcome, with the caveat that our project isn’t polemic but reportage, subject to fact-checking.

*

The syllabus is also an experiment, as much a course-reader-in-progress as a schedule. I’m sharing it with students week-by-week, to better accommodate the rapidly changing moment. Here’s week one:

The Reporters. Week One.

…I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail…

Swannanoa, North Carolina, after Hurricane Helene, 2024

By Adrienne Rich

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it is a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

From Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971–1972 by Adrienne Rich. Copyright © 1973 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Reading. For this Thursday:

1. The poem above.

2. “How to Escape Your Hometown,” by Claire Vaye Watkins, Lithub.

For next Tuesday:

3. “The Last Days of the Baldock,” by Inara Verzemnieks, Tin House. (This isn’t online, but readers of Scenes from a Slow Civil War can find this astonishing work of reportage—I remember where I was, in a library, when I first read it, standing, having picked up a copy of Tin House casually and then stuck there for pages—in a collection called American Precariat: Parables of Exclusion, edited by 12 incarcerated men from the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. There’s a summary of the piece here.)

4. Immersion: A Writer’s Guide to Going Deep, excerpts, by Ted Conover.

5. “Interviewing: Accelerated Intimacy,” by Isabel Wilkerson, in Telling True Stories, edited by Mark Kramer and Wendy Call

6. The Stakes of Telling a True Story, Pt. 1: “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling,” and “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” by Donald Trump.

7. The Stakes of Telling a True Story, Pt. 2: “Ground Truth,” by Natasha Trethewey, and “World on Fire: Ted Genoways in Conversation with Natasha Trethewey,” Switchyard

Listening. In class: “What Now Sounds Like, the AI Isn’t Smart Edition,” by Erica Heilman, Rumble Strip. Thursday: “What Now Sounds Like,” and “What Now Sounds Like, 2. Whales, Wrestling, and Customer Service.” Rumble Strip. (Take note of what moves you, puzzles you, reverberates with you.)

Writing: We’ll be working throughout the term toward a long, reported, narrative story about the strange contingencies of this particular moment in time in this particularly strange place—the Upper Valley of New Hampshire, and Vermont, broadly speaking. Our assignment each week is to complete at least 4-5 pages toward that end. Your assignment this week is to begin: to step outside of your normal sphere, to, perhaps, speak with a stranger, to immerse yourself in the world of another, to record your impressions. A true story, of you, and a world which may be on fire, in the week between now and next Tuesday.

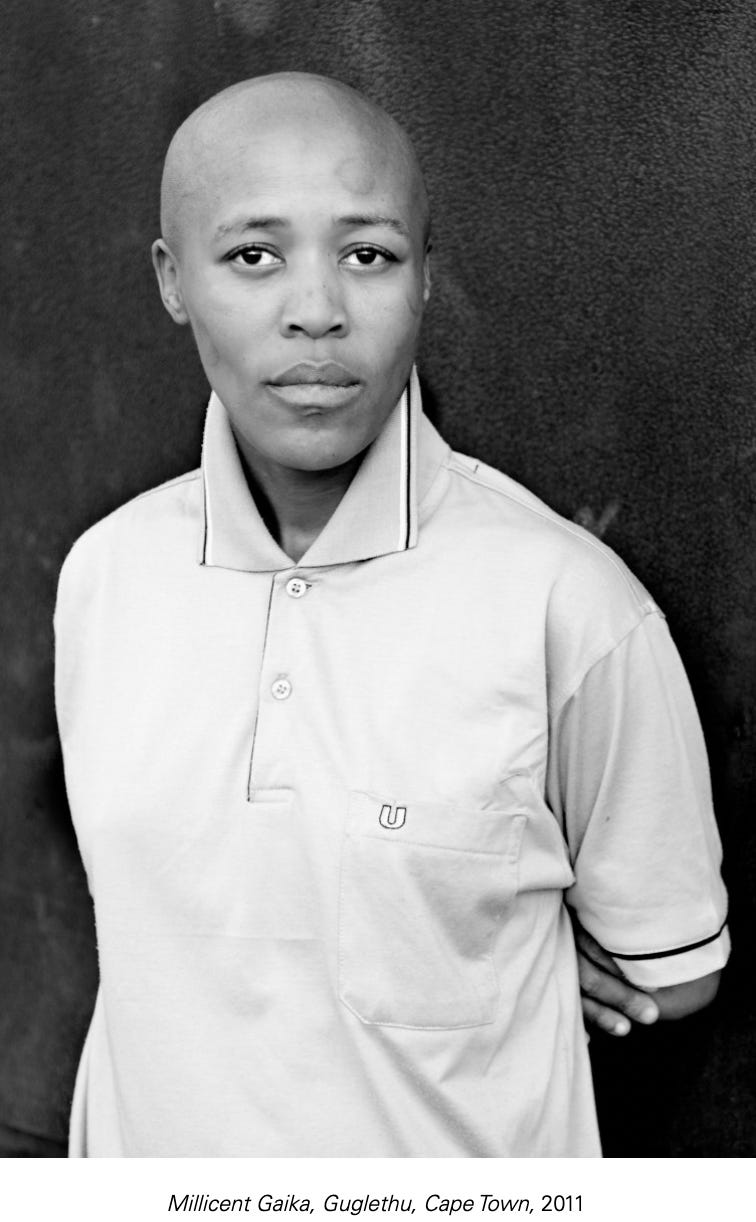

Looking: Last and not at all least, four portraits from the work of South African photographer Zanele Muholi, their project “Faces and Phases,” ongoing from 2006. In a week that begins with what appears to be the practical end of the Institute of Museums and Libraries—the government agency that, according to the American Library Association, provides “the majority of federal library funds,” and, in our regional public libraries, the support that has made possible interlibrary loan—we’ll begin with excerpts from an archive, Muholi’s documentation of Black South Africans lesbians. Why Black South African lesbians? Because they exist. That’s how this genre in which we’re writing this term works: A writer, a photographer, a documentarian—an artist—attends to that which draws their attention, and then thinks more deeply upon it and why and how it has drawn their attention, gathering evidence of existence, proof of the real, an archive of one artist’s perception.

I’ve chosen Muholi’s images for our first week because they’re brilliant examples of portraiture, of people in a place. Each image is simultaneously simple—a picture of a person, close-up—and infinitely complex. That’s the standard to which we’ll aspire.

Thank you so much for sharing this so those of us not able to take your class are able to follow along and glean some new insight, perspective and sanity!

this is a very good response to the current moment, to being present and thoughtful and seeing it. Look forward to the updates.